Is South Africa caught in a fiscal trap?

Over the past decade, the interest rate that South Africa pays on its debt has consistently been above the economic growth rate. Mathematically, this means that debt grows as a percent of GDP. It becomes a ‘vicious circle’. Higher debt makes investors and ratings agencies nervous, meaning the interest rate they are prepared to pay for our debt rises. This increases borrowing costs and hurts investment spending, making fiscal consolidation (and counter-cyclical fiscal policy) more and more difficult, making the fiscal position worse and raising the sovereign risk premium. The interest rate rises again, and the cycle continues.

Balancing development and fiscal consolidation

National Treasury is keenly aware of this – and of the trade-off between services and fiscal consolidation. The Budget Review earlier this month put it plainly: “The 2024 Budget balances development and sustainable public finances. In the context of persistently low economic growth, government will protect critical services, support economic growth through reforms and public investment, and stabilise public debt… Rapid growth in debt-service costs chokes the economy and the public finances. Government is staying the course to narrow the budget deficit and stabilise debt. This year, for the first time since 2008/09, government will achieve a primary budget surplus. Debt will stabilise in 2025/26.”

There has been a clear commitment to a fiscal strategy that aims to stabilise debt by targeting a primary surplus to ensure revenue exceeds non-interest spending. At the same time, the government’s core responsibility is to efficiently and equitably redistribute resources to provide for the most vulnerable, provide critical services, and safeguard economic growth through prudent fiscal management. Yet, despite a clear fiscal strategy why is fiscal sustainably so far from reach?

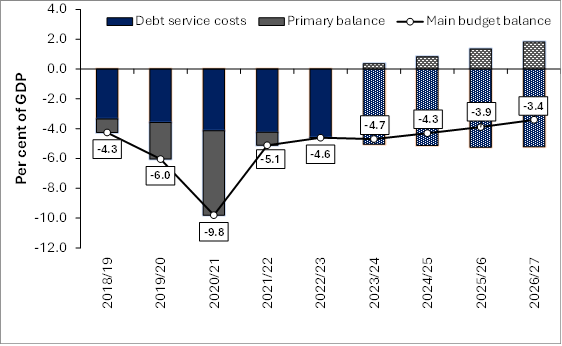

A snapshot of the main budget framework in the figure simplifies the fiscal position. South Africa has for several years run a primary deficit. Over and above a rising stock of debt the consistent expenditure pressure has not been matched by revenue, adding to the stock of debt. The net impact is ever-increasing debt servicing costs and a consistently wider main budget deficit. The first way to pull the fiscal position back on track is to turn the primary deficit into a primary surplus. Treasury projects this will happen in 2023/24 (although the accounting for Eskom makes this a little bit of stretch). They hope for a primary surplus for the foreseeable future. However, debt service costs will continue to grow, absorbing a larger share of the budget than basic education, social protection, and health. As it stands, debt service costs account for 20 cents out of every rand spent by the government. In this respect, government spending is too high for a revenue base weakened by delayed economic reforms, leaving Treasury little choice but to cut spending

Figure – Main budget framework (per cent of GDP)

Aiming for stability amid challenges

Despite presenting a hard line on the fiscal strategy, non-interest expenditure pressures, like renewed wage bill increases, have kept the primary deficit out of check for longer than necessary. The primary surplus is a step in the right direction. However, given the stock of debt and high-interest payments, the pain of short-term measures is only expected to provide gradual gains over the long term. An unsustainable fiscal position will reflect a rising debt-to-GDP ratio, which is associated with higher yields. As such, weak fiscal credibility raises the sovereign risk premium, which, in turn, leads to higher interest costs and worse fiscal outcomes.

So how did South Africa stumble into this fiscal trap? Indeed, several reasons outside of the control of the fiscal authority: state capture, weak electricity capacity and anaemic growth. That said, there are important factors under the control of government that have proven insufficient such as the use of a loose “fiscal rule” for targeting a nominal non-interest expenditure ceiling. The nominal non-interest expenditure ceiling lacks a credible anchor and so price effects, such as inflation, can unintentionally raise the ceiling between budget publications allowing expenditure to drift off course. For example, with a nominal expenditure ceiling, if projected inflation is reduced downwards, projected real spending rises for a given nominal ceiling. A common international approach is to use expenditure-to-GDP as the fiscal instrument or a real expenditure rule to meet a fiscal target of a stable debt-to-GDP ratio.

In our paper for the Southern Africa Towards Inclusive Economic Development SA-TIED programme, we explored the question of what to do when the long-term interest rate on government borrowing is greater than the long-term economic growth rate. We estimate the primary surplus required to stabilise debt and find that the Treasury will need to achieve and maintain its projected primary fiscal surpluses if it wants to counteract rising interest rates on government debt.

When the cost of government borrowing is lower than the economic growth rate a country can achieve a stable or declining debt-to-GDP ratio despite a moderate negative primary balance. In South Africa, however, the cost of borrowing exceeds the economic growth rate, which implies the debt-to-GDP ratio since 2016/17 started rising without limit as debt rose faster than GDP.

Growth in the South African economy is weighed down by persistent structural constraints and exacerbated by a delayed and reactive response to the implementation of economic reforms. Production in any economy requires electricity to power the machines that produce goods. Those goods then need well-functioning railway lines and ports to move goods between buyers and sellers. South Africa’s functioning economic infrastructure has faded away given the gradual deterioration in critical maintenance and failed attempts of building replacement infrastructure. The result is an economy with insufficient electricity supply to meet growing demands and rail and port inefficiencies that restrict the movement of goods. As a result, economic growth remains weighed down by persistent and unresolved domestic structural constraints that place an upper limit on economic growth.

Simply put, expenditure is currently too high for the revenue base. The consequences of greater government consumption expenditure and limited scope for revenue generation have led to a greater debt burden and increasing debt-service costs.

Treasury's efforts, risks, and proposed reforms

National Treasury is showing some resolve to stay the course in implementing a credible fiscal consolidation strategy that could reduce debt servicing costs. Under moderate assumptions, the Treasury can maintain a primary balance that keeps debt growth reasonably flat. However, the debt burden will not be reduced in the near term given the National Treasury expects the budget deficit to fall moderately from -4.9 per cent in 2023/24 to -3.4 per cent in 2026/27. The near-term outlook remains negative and highlights how precarious the long-term fiscal position remains, with debt-service payments projected to remain flat at 5.2 per cent of GDP by 2026/27. Indeed, the risk to the Treasury is that long-term interest rates will unexpectedly rise further and cause debt-service costs to spiral out of control—the classic case of a sovereign debt crisis is busy playing out in real-time. While the 2024 Budget Review shows that the National Treasury understands how important it is to get to a primary surplus and urgently implement critical economic reforms. We propose more is done to restore fiscal credibility through a stricter rule, specifically mapping a path for real government consumption spending. There is a narrow achievable window with several risks.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.