What happens when you tax the rich?

South Africa faces a dual challenge of limited fiscal space—the need to raise sufficient revenues to finance public services—and high levels of inequality. One possible solution is to raise tax rates on the rich. If successful, such reforms could increase revenues and mitigate income inequalities.

In 2017, South Africa raised the top marginal tax rate for annual incomes exceeding ZAR 1.5 million (about USD 78,000) from 41% to 45%. The change affected the top 0.6% of earners. Announced just days before implementation, the reform prevented income shifting to the previous tax year's lower rate. To prevent revenue leaks due to corporate owners evading taxes by paying dividends to their shareholders, the government raised the dividend tax rate as well.

How rate increases influence revenues depends on how taxpayers’ behaviour responds and, of course, also on how broad the tax base is. In South Africa, it is very broad. It lacks many common international deductions like those for children, student loan interest, or mortgage interest, which people may exploit to reduce their tax bill. Public finance analysts commonly expect that, in income tax systems with broad tax bases, opportunities for tax avoidance are kept at bay and rate increases should therefore increase revenue.

Based on the relatively strong implementation of the reform and the received wisdom about how the tax base influences taxpayer behaviour, one might have been optimistic that the South African income tax increase would help the country improve revenues and reduce income inequality.

The impacts of the 2017 top tax rate increase

In our latest SA-TIED Working Paper we examine the change in reported income after implementation of South Africa’s personal income tax reform for two groups of income taxpayers: those with earnings above ZAR 1.5 million and therefore affected by the rate increase, and those below the ZAR 1.5 million threshold (incomes between ZAR 700,000 and ZAR 1.5 million); a comparison group. After the reform, the amount of income reported by top-income earners above the threshold dropped sharply. In fact, it dropped so much that revenues collected on personal incomes above the ZAR 1.5 million threshold were less than they would have been without the reform.

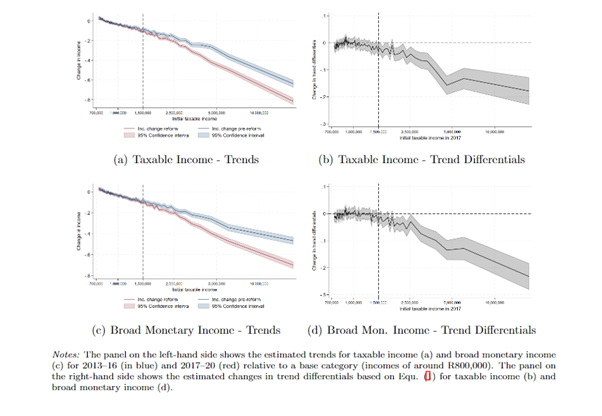

Figure 1 shows income trends before and after the reform. Relative differences in income growth are similar for the control group in both periods. The reductions in income growth for top earners are substantial in the period affected by the tax increase, around 10% and increasing with income earned. Additional checks confirm that income growth differences between higher and lower earners remained constant before the reform, which supports our understanding that Figure 1 captures the causal effect of the tax reform and no other factors, such as macroeconomic changes. This evidence shows that the reported incomes of those subject to the higher tax rate fell so substantially that the scope of the reform to increase revenues or address income inequalities was severely reduced.

Figure 1: Main results

How high are tax elasticities in South Africa?

Extensive research examines taxpayer responses to tax reforms, often focusing on the elasticity of taxable income (ETI). A meta-analysis of 61 studies and more than 1,700 ETI estimates puts ETI at 0.4. ETI measures the relative change in reported taxable income in response to a 1% change in the marginal net-of-tax rate (the income that taxpayers retain after taxes). For example, an ETI of 0.4 implies that if the net-of-tax rate decreases by 10%, the reported taxable income drops by 4%. Our estimates for South Africa translate into high tax elasticities, both before and after deductions, well above 1. These elasticities of taxable income (ETIs) are substantially higher than the ‘consensus’ estimates derived from existing work, i.e., the mean estimates of earlier research which focuses on higher-income countries. In fact, these ETIs are so large that they put the South African top tax rate on the wrong side of the so-called Laffer curve maximum. This means that tax revenues collected from the high-earner group declined when top tax rates increased.

Changes in tax revenues in response to changes in tax rates are often larger at the top of the income distribution. This is because top-income earners have more options for reducing their tax burden compared to other income earners. Research in the Deaton Review reveals that changes in reported income are modest for most employees when rates change but can be substantially higher for top earners. This is especially true for business owners. A lot of the high responsiveness to tax is due to business owners shifting income across tax bases, periods of time, or people to avoid paying more taxes. While such opportunities are limited in South Africa, there are some legal ways to lower tax burdens. For example, a high-earning manager might choose to receive part of their compensation as a contribution to a retirement fund rather than a cash bonus.

The impact on company performance

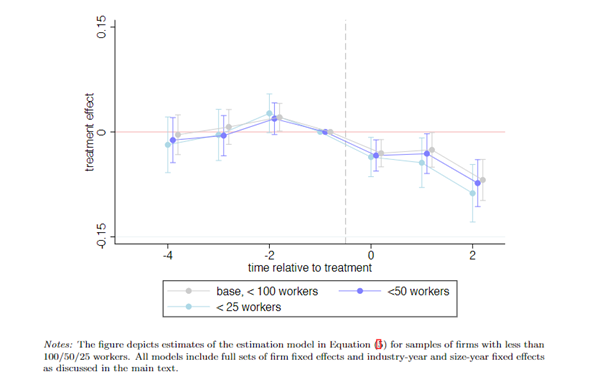

We also examine which income components saw the largest reductions. Such analysis is needed to understand what drove the drastic reductions in reported income. While normal monthly earnings did not decline, bonus payments, fringe benefits, investment income, and allowances—significant for high earners—sank strongly. We checked if top-earners completely disappeared from the tax net after the reform—by emigrating for example—but found no indication of this. To understand the broader implications for the South African economy, we were curious to know if these impacts were due to tax evasion, reduced work effort by high-income earners, or other factors. We looked at the output of companies with employees affected by the tax increase. Compared to similar non-affected companies, the affected companies saw reduced sales and value added (Figure 2). This suggests that the reform impacted companies’ economic performance, and that tax reporting behaviour alone does not fully explain the response.

Figure 2: Impact on sales of firms where individuals with the higher tax work

Our research shows that when you tax the incomes of the rich in lower-income countries, like South Africa, this can be counterproductive even when design and implementation are done well. We found that while some wealthy individuals may use tax planning to reduce their tax burden, this isn't the only issue. High income taxes can also negatively impact the performance of companies. These findings highlight the need for tax authorities to carefully analyse the impact of tax reforms and continue to calibrate tax policy.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.